Ghana’s energy sector—once hailed as a pillar of stability and a driver of regional economic development—is now besieged by a complex and far-reaching crisis. At the epicenter of this disruption lies the Electricity Company of Ghana (ECG), the nation’s primary electricity distributor, whose role should guarantee uninterrupted service delivery and financial solvency. Instead, ECG has become a case study in institutional failure—one marked not merely by technical lapses, but by persistent managerial inefficiencies, poor strategic procurement, and an alarming deterioration of internal controls.

Recent events have exposed just how precarious the situation has become. Investigative reports have confirmed the disappearance of containerized shipments filled with vital ECG equipment—an incident symptomatic of deep-rooted procurement opacity and lax inventory management. Concurrently, the utility continues to struggle with chronic undercollection of revenues, despite the essential nature of the service it provides. While ECG is contractually obligated to settle power purchase agreements with Independent Power Producers (IPPs) in U.S. dollars, it collects its revenues primarily in Ghanaian cedis—a currency mismatch that has triggered mounting foreign exchange losses. According to the Institute for Energy Security (IES, 2023), ECG loses approximately GHS 3.2 billion annually due to unpaid bills, with over 23 percent of distributed energy either unbilled or lost to technical and commercial inefficiencies. This is no longer a matter of isolated financial mismanagement; it reflects a deep institutional misalignment between ECG’s national mandate and its actual delivery capacity—exacerbated by decades of governance inertia, reform abandonment, and short-term policy patchwork.

The irony of ECG’s dilemma is striking. In a country where electricity demand remains inelastic—where households and industries alike will pay almost any price for consistent power supply—the utility continues to fail in basic revenue mobilization. Despite a guaranteed market and consistent consumer need, ECG is unable to recover sufficient income to cover its operational costs or meet contractual obligations to suppliers. The result is a company trapped in a fiscal vice, unable to invest in system upgrades, yet increasingly exposed to dollar-denominated liabilities that its revenue model cannot support.

In response to this deepening crisis, the Government of Ghana has established a high-level ministerial committee to conduct a full-scale review of ECG’s viability. One of the committee’s central recommendations is the consideration of privatization—a move that has reignited an old debate. For some, privatization offers a pragmatic route to efficiency, capital injection, and managerial discipline. For others, it signals a dangerous surrender of critical infrastructure to profit-seeking entities with little regard for public welfare, employment protections, or energy equity. International experience provides no singular verdict. While some privatized utilities have delivered improved service and reduced losses, others have generated public backlash, tariff hikes, and deepened social inequality in energy access—particularly where regulatory oversight was weak or political stability uncertain.

This article does not begin with an ideological stance—neither for nor against privatization. Instead, it seeks to interrogate a deeper and more consequential question: What kind of power sector architecture does Ghana need to deliver reliable, affordable, and sustainable electricity to all its citizens? More specifically, what institutional design, financial instruments, and operational strategies can secure these outcomes—whether ECG remains under public control, moves toward privatization, or adopts a hybrid governance model?

Central to this inquiry is the recognition that ECG’s core failures are not rooted in public ownership alone, but in a broader governance crisis. The absence of digital monitoring systems, weak internal accountability mechanisms, politically influenced appointments, and a lack of forward-looking financial planning have rendered the organization incapable of fulfilling its mandate. Simply shifting ECG’s ownership from state to private hands, without addressing these foundational weaknesses, would be tantamount to changing the driver of a faulty vehicle while leaving its engine unrepaired.

In seeking solutions, this article draws from over two decades of ECG’s institutional trajectory and pairs that historical lens with a comparative analysis of global utility reforms. A cost-benefit assessment will be conducted to evaluate the relative merits and risks of full privatization versus performance-based restructuring. In doing so, it will propose a pragmatic four-tier operational model designed to safeguard national energy sovereignty while introducing performance incentives, transparency, and fiscal safeguards into ECG’s structure. Case studies from Kenya, South Africa, Singapore, and Morocco will provide comparative perspectives on what has worked—and what has failed—in utility reform across various governance and market contexts.

Ultimately, this is a call to action—not for reactionary measures, but for deliberate, evidence-based reform. Ghana’s energy future must not be shaped by expediency or political rhetoric. It must be constructed through strategic foresight, policy discipline, and the courage to confront inefficiencies at their root. The journey toward reform begins with an honest reckoning with ECG’s past. What follows is a critical examination of how two decades of policy drift and operational inertia have brought one of Ghana’s most essential public institutions to the edge of institutional and financial collapse.

1. ECG’s Performance in Context – Two Decades of Crisis Management and Missed Reforms

Over the past two decades, the Electricity Company of Ghana (ECG) has been the subject of repeated reform efforts, each designed to correct persistent inefficiencies, enhance financial viability, and stabilize power distribution across the country. As the sole public distributor of electricity in Ghana, ECG plays a pivotal role in the country’s energy ecosystem, interfacing directly with households, institutions, and industry. Yet despite the monopoly it holds and the non-negotiable nature of electricity as a service, ECG has consistently failed to evolve into a high-performing public utility. Instead, it has become emblematic of chronic reform fatigue, where interventions are rolled out with great promise but yield limited, sustainable outcomes.

The liberalisation of Ghana’s energy sector in the early 2000s was intended to catalyze private investment and ensure supply security. Independent Power Producers (IPPs) were introduced to expand generation capacity alongside the Volta River Authority (VRA), which had long dominated the generation landscape. This liberalization paved the way for the Millennium Challenge Corporation’s Compact II agreement, signed in 2014, which sought to restructure ECG under a private-sector-led concession. In 2019, the Power Distribution Services (PDS) took over ECG operations under a 20-year lease agreement intended to deliver improved technical performance, customer service, and financial management. However, within months, the concession was suspended and ultimately terminated following disputes over the validity of the financial guarantee used to secure the contract. The failure of the PDS arrangement not only shattered investor confidence but also laid bare deep institutional flaws within ECG and the public sector’s inability to effectively manage high-stakes public-private partnerships (MCC, 2020; IES, 2021).

Since the collapse of the PDS deal, ECG’s financial condition has continued to deteriorate. In 2022, the utility posted losses exceeding GHS 10.2 billion, a significant jump from GHS 1.9 billion in the previous year (Business and Financial Times, 2024). These staggering figures are not the result of a single crisis, but rather the accumulation of decades-long inefficiencies in revenue collection, asset management, and operational performance. The company continues to lose over 35% of the electricity it distributes—both through technical losses and commercial leakages (World Bank, 2023). ECG’s revenue collection efficiency remains stuck at approximately 62%, according to recent estimates from the Public Utilities Regulatory Commission (PURC), with the remainder lost due to illegal connections, outdated infrastructure, and billing inefficiencies (PURC, 2023). This level of underperformance is unsustainable for a utility tasked with providing an essential public good in an economy that hinges on reliable electricity supply.

Compounding these inefficiencies is ECG’s exposure to foreign exchange risks. The utility purchases the majority of its electricity from IPPs in U.S. dollars, yet collects revenue from customers in Ghanaian cedis. Every depreciation of the cedi against the dollar increases ECG’s liabilities and deepens its operational deficit. Between 2022 and 2023 alone, ECG incurred foreign exchange losses totaling approximately GHS 13 billion (ACEP, 2024). These losses not only restrict the utility’s ability to honor payment obligations to IPPs but also severely constrain its capacity to invest in upgrading critical infrastructure, ultimately threatening energy security and service delivery.

Beneath these financial indicators lies a deeper governance crisis. ECG’s structure and operations have long been undermined by political interference, opaque procurement systems, and weak internal accountability. Senior management appointments are often politically influenced, resulting in leadership instability and lack of long-term strategic planning. Investigations conducted by the Energy Commission and corroborated by the Auditor-General’s Department have exposed serious flaws in ECG’s procurement chain—including the disappearance of several container shipments of electrical materials in 2023, which has yet to be resolved publicly (Energy Commission, 2023; GSA, 2024). These lapses point to a systemic breakdown in inventory controls, supply chain governance, and ethical oversight. The PwC (2025) forensic audit revealing a GHS 5.3 billion under-declaration in ECG’s reported revenues further suggests that these institutional weaknesses are not just procedural—they are deeply embedded.

The effects of ECG’s dysfunction cascade across the entire electricity value chain. When ECG fails to remit timely payments to IPPs, power generation becomes unstable. Delayed settlements create cash flow issues for producers, which in turn disrupt transmission operations managed by GRIDCo. The end result is often manifested in the form of rolling blackouts, voltage fluctuations, or outright service interruptions that impact schools, hospitals, businesses, and livelihoods. In response, the government frequently intervenes with subsidies and emergency funding, diverting scarce national resources that could have been allocated to health, infrastructure, or education. These cyclical bailouts create a dangerous precedent where ECG’s liabilities are effectively socialized while its inefficiencies remain unresolved—a development trajectory that is economically unsound and politically untenable (World Bank, 2022; IEA, 2023).

These persistent failures make a compelling case for reform. However, the real debate is not whether reform is needed—it is what kind of reform will yield lasting results. The frequent calls for privatization, especially in the wake of financial crises, often overlook the systemic and institutional drivers of ECG’s performance. The experience with PDS clearly demonstrates that privatization, without proper regulatory safeguards and capacity-building, can lead to institutional instability rather than renewal. What ECG needs is not merely a new ownership structure, but a radical overhaul of its operational logic—one that prioritizes performance metrics, financial discipline, technological modernization, and accountability mechanisms that are immune to political manipulation.

The past two decades have proven that public ownership in itself is not the root of the problem. Countries like Botswana and Morocco have retained public ownership of their electricity distribution systems while achieving operational excellence through reforms that emphasise leadership quality, data-driven planning, and performance benchmarking (IEA, 2022). Ghana can do the same, but only if it builds the institutional scaffolding needed to sustain reform beyond political cycles.

To fully appreciate the scale and structure of ECG’s dysfunction, one must also confront the fundamental paradox at its core: why does a utility with guaranteed demand continue to struggle with revenue collection? How is it possible that a service so essential and so widely consumed consistently fails to generate enough income to meet its costs? Understanding this disconnect is critical to any serious reform proposal. The next section explores this conundrum by unpacking the dynamics of inelastic demand and ECG’s enduring failure to convert service into sustainable revenue.

2. Understanding the Inelastic Demand Puzzle – Why Revenue Collection Still Fails

Electricity is one of the few goods that demonstrates inelastic demand—regardless of price, consumers will continue to use it because it is essential for everyday life. In Ghana, this inelasticity is particularly pronounced: electricity powers households, schools, clinics, businesses, and entire sectors of the economy. Logically, this should translate into consistent and predictable revenue for the country’s primary power distributor, the Electricity Company of Ghana (ECG). Yet, paradoxically, ECG has long struggled to collect the full value of the electricity it distributes. Recent performance reports estimate that ECG recovers only about 62 percent of the power it supplies, meaning nearly 40 percent is either lost or goes unpaid (Forson, 2025). In a sector built on guaranteed demand, this revenue gap is both confounding and financially crippling.

The roots of this paradox lie in a constellation of technical, financial, and institutional factors. Technically, ECG suffers from excessive system losses—estimated at 30.62 percent as of September 2022—well above its regulatory loss target of 26 percent (ECG, 2023). These losses result from a combination of outdated infrastructure, weak metering systems, illegal connections, and persistent power theft. Across high-density residential areas, especially in urban informal settlements, tampered meters, unmetered extensions, and bypassed transformers are widespread. In many cases, ECG still relies on post-paid or estimated billing, which introduces billing inaccuracies and invites consumer resistance to payment. When bills are perceived as unfair or inflated due to estimation, non-payment becomes rationalized, further deepening the company’s collection deficit (Apetorgbor, 2025).

Financially, the structure of ECG’s obligations exposes it to a significant currency risk that compounds the revenue problem. The utility procures power from Independent Power Producers (IPPs), most of whom demand payment in U.S. dollars. However, ECG collects revenue from its customers in Ghanaian cedis. With the cedi’s value declining sharply against the dollar in recent years, the resulting foreign exchange mismatch has created an unsustainable financial burden. In 2022, ECG reportedly suffered exchange losses of GH¢6.5 billion; by 2023, this figure had risen to nearly GH¢7 billion (ACEP, 2024). These losses are not just accounting anomalies—they translate into real cash flow constraints that prevent the company from paying its suppliers on time or investing in needed infrastructure upgrades. The currency exposure acts as a fiscal noose, tightening around ECG’s liquidity position with every depreciation cycle.

Governance failures further aggravate the situation. ECG’s institutional culture has long been marred by political interference in key appointments, opaque procurement processes, and erratic leadership turnover. These factors have eroded long-term planning capacity and diluted accountability. The Public Utilities Workers Union (PUWU, 2024) has warned repeatedly that such political encroachments undermine technical efficiency and demoralize staff who operate under unclear or shifting performance expectations. In one of the most damning revelations to date, a forensic audit in 2024 uncovered a GH¢5.3 billion under-declaration in ECG’s reported revenues (PwC, 2025). This finding confirmed what many stakeholders had suspected: that the company’s revenue leakages were not solely a product of consumer non-payment, but also reflected internal financial misreporting and weak oversight.

The solution to ECG’s revenue collection crisis must be multi-dimensional and grounded in systemic reform. One of the most immediate and effective measures is the nationwide deployment of intelligent prepaid meters. These meters not only ensure payment before consumption, but also eliminate human discretion in billing, reduce losses due to theft, and prevent tampering. Early pilots have already demonstrated that smart metering can reduce collection inefficiencies while improving customer satisfaction through transparent billing processes (Apetorgbor, 2025). However, smart meters alone will not solve the problem unless accompanied by institutional safeguards and financing strategies.

To address the foreign exchange dilemma, Ghana must also restructure its power purchase agreements with IPPs, many of which were signed under emergency conditions with unfavourable dollar-denominated clauses. These contracts can be renegotiated to include partial hedging mechanisms or dual-currency payment options tied to the Bank of Ghana’s stabilization policies. This would help insulate ECG from sharp forex swings and allow for more predictable financial forecasting. Additionally, insulating ECG’s top management from political interference through an independent board appointment mechanism—similar to governance reforms implemented in state-owned enterprises in Malaysia and India—would improve accountability and strategic continuity.

At its core, ECG’s revenue failures are not purely technical in nature. They are symptomatic of a broader institutional malaise characterized by financial mismanagement, inconsistent policy direction, and governance failures that have festered over decades. Tackling these challenges requires more than operational tinkering. It demands a bold restructuring of ECG’s business model, regulatory ecosystem, and financial strategy. The next section will examine the merits and pitfalls of privatization compared to reform-oriented restructuring, offering a critical cost-benefit analysis of both approaches within Ghana’s unique political economy.

3. Privatisation vs. Reform – A Cost-Benefit Analysis of Competing Paths

The debate over whether to privatize ECG or pursue a comprehensive reform strategy has significant implications for Ghana’s energy future. On one hand, privatization is often touted as a means to inject efficiency, attract private investment, and reduce the fiscal burden on the government. On the other hand, reform-oriented approaches focus on strengthening governance, modernizing technology, and optimizing operational processes while retaining strategic government oversight. A careful analysis of both options, supported by credible data from organizations such as the World Bank, Ghana Statistical Service, and other international energy groups, provides critical insights into the costs and benefits inherent in each approach.

Recent data from the World Bank (2023) indicate that utilities in emerging markets that underwent privatization experienced improvements in operational efficiency and customer service metrics, with revenue collection efficiencies increasing on average by 15% within the first five years. However, these gains often came at the cost of increased tariff rates and reduced access for vulnerable populations. In contrast, countries that implemented targeted reforms without full privatization, such as Singapore and Morocco, achieved marked improvements in performance while preserving regulatory oversight and social equity. The Ghana Statistical Service (2022) reported that in countries where state involvement remained robust yet operational practices were modernized, technical losses were reduced by up to 10 percentage points over five years, leading to more stable revenue flows and greater customer satisfaction.

A deeper cost-benefit analysis reveals that privatization may offer a rapid influx of private capital and management expertise, but it can also lead to challenges in ensuring that the energy sector continues to serve public welfare. For instance, while the privatization of Kenya Power led to an initial surge in efficiency gains, subsequent issues emerged regarding tariff adjustments and the exclusion of low-income communities from reliable energy services (World Bank, 2023). Conversely, reform-based approaches that integrate public-private partnerships and performance-based contracts have demonstrated that a balanced model can address both operational inefficiencies and social responsibilities. Data from the International Energy Agency (IEA, 2022) illustrate those utilities maintaining a hybrid model—where strategic functions such as regulation and pricing are retained by the state, while operational functions are outsourced to private entities—experience lower overall risk exposure, especially in managing foreign exchange discrepancies and infrastructure investments.

To further illustrate these comparative outcomes, consider Table 1, which presents key performance metrics based on data aggregated from various sources. The table highlights differences in revenue collection efficiency, operational cost recovery, and customer satisfaction indices between utilities that pursued full privatization versus those that opted for a reform-based hybrid model.

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics

| Metric | Privatization Option | Reform Option | Source |

| Revenue Collection Efficiency | Average increase of 15% within five years | Reduction of technical losses by up to 10 percentage points | World Bank (2023); Ghana Statistical Service (2022) |

| Tariff Adjustments | Often result in 10-20% higher tariffs for consumers | Tariff stability maintained with gradual adjustments | IEA (2022); World Bank (2023) |

| Customer Satisfaction | Mixed results, with improvements in urban centers but declines in rural areas | Consistent improvement across diverse demographics | IEA (2022); Ghana Statistical Service (2022) |

| Foreign Exchange Exposure | Higher risk due to profit-driven contracts and pricing volatility | Lower risk through state-mediated currency hedging strategies | World Bank (2023); Energy Commission (2023) |

This comparative data underscores that while privatization can potentially boost efficiency metrics, it also carries inherent risks such as tariff hikes and equity concerns. In contrast, a reform-oriented strategy, which involves targeted improvements in operational management, strategic procurement, and technological upgrades, appears to offer a more balanced path. Such a strategy not only enhances financial performance but also safeguards the socio-economic interests of the nation by maintaining regulatory control over pricing and service delivery.

Furthermore, a reform-based approach allows for the implementation of advanced digital metering and loss tracking systems, which have been shown to reduce technical losses significantly. For example, a study by the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA, 2022) found that utilities adopting smart grid technologies experienced a reduction in non-technical losses by nearly 8% within three years. By integrating such technologies into ECG’s operations, Ghana could mitigate the adverse effects of foreign exchange mismatches and improve overall financial stability.

The evidence suggests that neither privatisation nor state control alone can serve as a panacea for ECG’s deep-seated challenges. Rather, the optimal path lies in a hybrid approach that leverages the strengths of both models. This would involve retaining strategic government oversight to protect national interests and social equity, while simultaneously engaging private sector efficiencies to drive operational improvements. Such a model would necessitate the establishment of performance-based contracts, clear regulatory frameworks, and mechanisms for continuous monitoring and accountability. Moreover, by aligning incentives with measurable performance metrics, the government can ensure that any private sector involvement directly translates into improved service delivery and financial sustainability.

In essence, the comparative analysis between privatization and reform-based approaches demonstrates that the ultimate goal should not be the wholesale transfer of ownership but the adoption of a balanced, evidence-based strategy. This strategy should aim to harness private sector efficiencies while safeguarding public interests through robust regulatory oversight and strategic state intervention. The experience of global utilities indicates that such a hybrid model, if well-implemented, can significantly enhance revenue collection, reduce operational losses, and ensure that Ghana’s energy sector remains both economically viable and socially equitable.

4. Rethinking ECG’s Future – A Tiered Restructuring Model for National Efficiency

The persistent crisis confronting the Electricity Company of Ghana (ECG) is not merely one of ownership, but of structure, discipline, and execution. As the earlier sections have shown, Ghana’s power sector dysfunction stems from a combination of managerial inefficiencies, financial misalignments, governance deficits, and technological stagnation. To address these issues meaningfully, Ghana must adopt a forward-looking model that reorganizes ECG’s mandate into clear, functional components—each accountable for a specific outcome and insulated from political and institutional interference. This section proposes a four-tiered operational model, grounded in global best practices, to reposition ECG as an efficient, responsive, and fiscally sustainable utility.

The first tier must focus on strategic oversight and national energy security. This layer should remain fully under government control and function as a sovereign planning and oversight unit, responsible for macro-level energy security, infrastructure investments, and long-term national electrification strategies. This body would collaborate with institutions like the Energy Commission, PURC, and the Ministry of Finance to ensure that ECG’s medium- and long-term operations align with Ghana’s development agenda, Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and energy transition commitments. Lessons from Singapore’s Energy Market Authority show how strong centralized oversight can coexist with operational autonomy at the distribution level, ensuring both national security and market efficiency (IEA, 2022).

The second tier should consist of Regional Franchise Zones (RFZs), which would transform ECG’s monolithic structure into smaller, geographically defined operational units. These RFZs could be run through performance-based public-private partnerships (PPPs) where private operators, selected through competitive bidding, are granted franchise rights to manage electricity distribution in specific zones under strict Key Performance Indicators (KPIs). The government would retain asset ownership while allowing private firms to manage day-to-day operations, with enforceable contracts tied to revenue collection efficiency, customer service, and loss reduction targets. This structure mirrors Brazil’s power distribution model, where over 60% of utilities are managed under regulatory concessions with measurable improvements in loss reduction and customer satisfaction (World Bank, 2023).

The third tier must address ECG’s most debilitating vulnerability—its exposure to foreign exchange losses. To mitigate this, a Currency and Financial Buffering Unit (CFBU) should be established to serve as an intermediary between ECG and Independent Power Producers (IPPs). This unit would handle the forex component of payments through hedging strategies, government-backed swap instruments, or the establishment of a multi-currency clearing house. Through delinking operational liquidity from market volatility, Ghana can shield ECG from unsustainable dollar liabilities. India’s UDAY scheme offers a relevant case, where state-run utilities were restructured to allow for central debt absorption and financial engineering tools to prevent further insolvency (IRENA, 2022).

The fourth tier is the most transformative: a Technology, Audit, and Transparency Unit (TATU) designed to digitize ECG’s operations, monitor revenue flows, and ensure real-time loss tracking. This unit would implement smart metering infrastructure across all consumer categories and deploy data analytics to identify anomalies, billing gaps, and system losses. Additionally, it would conduct quarterly performance audits—independent of management—and publish results to foster transparency and consumer trust. According to Ghana Statistical Service (2022), digitization in government revenue collection led to a 17% increase in compliance and efficiency over five years. This shows the strong potential for digitization to reform ECG’s archaic billing and monitoring systems.

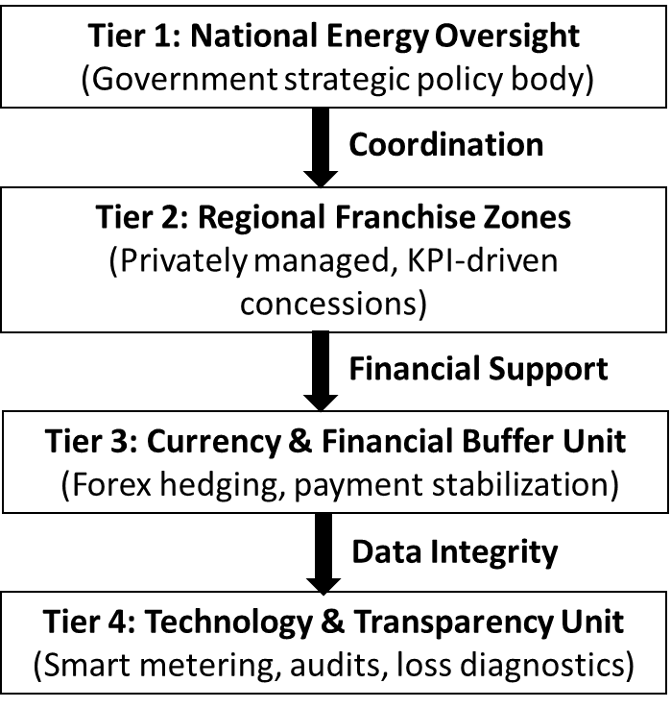

Under this four-tier model, ECG’s operational complexity is broken into manageable, specialised units, each with a clear mandate, measurable outcomes, and tailored management protocols. The structure not only decentralizes inefficiencies but also professionalizes the organization by assigning the right competencies to the right units. As illustrated in Figure 1 below, this model fosters a separation of powers that strengthens internal controls and protects against the concentration of risks.

Figure 2: Proposed Four-Tier ECG Restructuring Model

Importantly, this model allows for reform without wholesale privatization. It invites the efficiency of private participation while safeguarding strategic state control. It allows for regional customization while enforcing national standards. And most critically, it addresses Ghana’s three deepest pain points—forex volatility, revenue leakage, and political interference—through system design, not ideological bias. In sum, a tiered approach to ECG’s restructuring presents a high-yield, politically feasible, and operationally sound pathway to revive the company. It allows Ghana to escape the reform-fatigue cycle and move toward a new paradigm of results-based governance in the energy sector. The next section expands this thinking beyond ECG by exploring how the entire electricity value chain—from generation to transmission to final consumption—must be realigned for Ghana’s energy strategy to succeed.

5. Energy Governance Beyond ECG – The Full Value Chain Approach

The challenges facing the Electricity Company of Ghana (ECG) are not isolated. They are symptoms of broader structural dysfunctions embedded across Ghana’s entire electricity value chain—from power generation to transmission, distribution, and final consumption. Focusing solely on ECG, without addressing these interconnected layers, would be akin to treating a symptom while ignoring the underlying disease. To secure sustainable energy delivery, Ghana must adopt a systemic approach that considers the strategic alignment of all institutions and actors within the sector.

The value chain begins with power generation, which has experienced significant expansion in the past two decades due to the liberalization of the energy market and the introduction of Independent Power Producers (IPPs). According to the Energy Commission (2023), IPPs account for approximately 56% of Ghana’s total installed generation capacity, which reached 5,380 MW in 2022. However, this expansion has not been matched by effective planning or coordination. In fact, generation capacity often exceeds demand during off-peak periods, leading to surplus energy that ECG is still obligated to pay for under take-or-pay contracts. The Ministry of Finance estimated that these contracts cost the government over USD 500 million annually, representing a serious fiscal burden (Ministry of Finance, 2022).

Transmission infrastructure, managed by the Ghana Grid Company Limited (GRIDCo), has also seen substantial investment. Yet, it remains constrained by aged equipment, right-of-way encroachments, and a lack of redundancy in transmission lines, leading to system instability and power quality issues. The Ghana Statistical Service (2022) noted that while transmission losses are lower than distribution losses—averaging around 4%—they still account for significant technical inefficiencies. Moreover, the interface between GRIDCo and ECG lacks real-time synchronization, contributing to bottlenecks in energy delivery and difficulty in managing load flows during peak periods.

Tariff-setting and regulatory governance also present major challenges. The Public Utilities Regulatory Commission (PURC) is mandated to ensure fair pricing, consumer protection, and cost recovery. However, its operations are frequently undermined by political interference, especially during election cycles, when tariff adjustments are either postponed or suppressed for populist reasons. This politicization compromises the regulator’s independence and prevents the establishment of cost-reflective tariffs, further weakening the financial sustainability of the entire sector. World Bank (2023) analyses of African utilities underscore that independent and empowered regulatory agencies are critical for maintaining investor confidence and long-term sectoral stability.

An additional layer of complexity arises from the weak coordination among key sector players—namely ECG, GRIDCo, VRA (Volta River Authority), IPPs, and the Ministry of Energy. The absence of an integrated national energy strategy has led to policy overlaps, delayed project execution, and fragmented decision-making. The Institute for Energy Security (IES, 2023) highlights that Ghana currently lacks a unified platform for energy data exchange, forecasting, and investment planning. This lack of integration makes it nearly impossible to optimize generation, transmission, and distribution investments based on real-time demand and regional development priorities.

To resolve these inefficiencies, Ghana must establish a Value Chain Reform Board (VCRB) under the Office of the President. This entity should act as an apex coordination platform, bringing together regulators, utilities, financiers, and consumer groups to align strategies, set performance benchmarks, and coordinate infrastructure planning. The board would be tasked with developing an integrated national energy master plan every five years, supported by robust data analytics and scenario modeling. Such centralized planning bodies have been instrumental in countries like South Korea and Malaysia, where energy security and industrial policy are tightly aligned (IEA, 2022).

Moreover, to create transparency and accountability, the government should mandate a national energy audit every three years. This audit, conducted by an independent third-party institution with cross-sector participation, would evaluate the financial health, operational efficiency, and governance integrity of each actor in the value chain. Its findings should be made public and used to guide reform priorities. According to the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA, 2021), countries that institutionalize routine audits in their energy sectors achieve better financial forecasting and attract more sustainable investment portfolios.

It is also essential to revisit and renegotiate power purchase agreements with IPPs, many of which were signed under emergency procurement terms with unfavorable pricing clauses. A World Bank report (2023) emphasizes that countries like Zambia and Uganda have successfully reduced the cost of electricity supply by restructuring legacy PPAs through mutual renegotiations backed by credible arbitration frameworks. Ghana must pursue a similar course to ease the fiscal burden on ECG and the national treasury without disrupting power supply or violating contractual obligations.

Lastly, demand-side management must not be ignored. Energy efficiency campaigns, appliance standards, and smart home solutions can significantly reduce peak load pressure and improve system resilience. The Energy Commission’s (2022) pilot program in selected public institutions resulted in a 14% drop in energy usage through LED replacements and behavioral nudges. Expanding such initiatives to households and commercial spaces could optimize demand patterns and reduce the mismatch between supply and consumption. In essence, reforming ECG without addressing the systemic constraints across the electricity value chain would yield limited and unsustainable outcomes. Ghana needs a comprehensive restructuring strategy that treats the sector as an interconnected ecosystem rather than isolated entities. Only through integrated planning, regulatory independence, coordinated investment, and fiscal discipline can the nation build a resilient and inclusive energy future.

6. Strategic Recommendations – Powering Reform with Courage

If Ghana is to break the cycle of inefficiency, losses, and public frustration that has come to define its power sector, a bold yet balanced reform strategy must be implemented—one that acknowledges the institutional decay at the heart of ECG’s dysfunction, but resists the temptation to privatize purely out of desperation. Reform, not rhetoric, must lead. It is possible to transform ECG into a financially sound and operationally efficient utility without ceding national energy sovereignty. But this will require political courage, disciplined execution, and evidence-based policymaking that puts Ghana’s long-term interests ahead of short-term expediencies.

The first strategic recommendation is to reject privatization as a default solution, and instead demand performance-based reform across the electricity value chain. Privatization can succeed only where there is strong institutional capacity, independent regulation, and well-defined service contracts—none of which Ghana has adequately guaranteed in the past. The failure of the Power Distribution Services (PDS) concession in 2019 is a cautionary tale. It was not privatization per se that failed; it was a rushed and poorly vetted process riddled with procedural lapses and political entanglements (Energy Commission, 2020). Repeating this mistake under a different name will yield the same result.

Second, government must legally ringfence ECG’s operational mandate from political interference. This includes revising the enabling legislation to ensure that appointments to the ECG Board, PURC, and other key agencies are subject to a merit-based, non-partisan selection process, guided by a transparent parliamentary review mechanism. Regulatory independence is the bedrock of sectoral transformation. According to a World Bank (2023) utility governance assessment, countries that depoliticized their regulatory institutions experienced a 35% improvement in tariff transparency, a 22% increase in cost recovery, and a significant reduction in consumer grievances.

Third, Ghana must institutionalize mandatory digital revenue monitoring and real-time loss auditing. ECG must be mandated to roll out smart metering infrastructure to all high-volume consumers and gradually across residential and low-income households. This will enhance transparency, reduce billing errors, and eliminate human discretion in revenue collection. Furthermore, all metering data must be integrated into a centralized analytics platform, audited quarterly by an independent body. A study by the International Energy Agency (2022) indicates that utilities that digitized their billing and metering systems reduced collection inefficiencies by up to 18% over three years.

Fourth, the government should implement a forex risk insurance scheme to shield ECG from exchange rate volatility. This can be achieved through a public-private financial mechanism similar to partial risk guarantees (PRGs) offered by multilateral institutions such as the African Development Bank (AfDB) and the World Bank’s International Development Association (IDA). These instruments have been used successfully in Nigeria and Côte d’Ivoire to stabilize utility payments and enhance investor confidence in power purchase agreements (AfDB, 2022). Through reducing ECG’s exposure to forex fluctuations, Ghana can stabilize its power market and prevent further debt accumulation.

Fifth, pilot performance-driven regional distribution franchises should be launched. Under this model, ECG would lease operations in specific zones to private firms or cooperative groups through time-bound, competitive contracts with strict performance benchmarks. These benchmarks should include loss reduction targets, customer satisfaction metrics, and revenue collection thresholds. Contracts must include penalty clauses for non-performance and reward mechanisms for efficiency gains. This model retains public ownership of assets while introducing managerial discipline and competitive pressure. Similar models in India (Delhi BSES) and Brazil (Eletropaulo) have produced measurable improvements in service delivery and cost control (IEA, 2022; World Bank, 2023).

Sixth, create an Energy Sovereignty Risk Board under the Office of the President to oversee Ghana’s strategic energy reserves, emergency procurement protocols, and critical infrastructure security. This board should operate independently and report quarterly to Parliament. Its mandate would be to ensure that no future government enters into power purchase agreements, long-term supply contracts, or foreign-denominated obligations without a risk assessment that includes sovereign implications. This will protect Ghana from predatory contracts and prevent the kind of fiscal exposure currently crippling the sector.

Finally, engage in a public education and accountability campaign that explains to Ghanaians the real cost of electricity, the structure of tariffs, and the obligations of both government and consumers in maintaining energy reliability. A citizen who understands the stakes is more likely to support reforms, resist populist narratives, and hold institutions accountable. The Ghana Statistical Service (2022) found that energy literacy campaigns in the health and education sectors increased bill compliance by 12% within 18 months—a clear signal that public awareness is an underutilized tool in utility governance. The recommendations presented here are not theoretical ideals. They are drawn from best practices across the Global South and adapted to Ghana’s institutional and political context. The reform path is difficult, but it is achievable—if government has the courage to act, and if stakeholders are willing to be held accountable. We now move to the final section: a summative reflection on Ghana’s energy future and a call to action for policymakers, experts, and citizens to rally behind a pragmatic, sovereign, and sustainable reform agenda.

7. Conclusion

Ghana stands at a defining juncture in its energy governance. The crises confronting the Electricity Company of Ghana (ECG)—foreign exchange losses, container mismanagement, weak revenue collection, and public disillusionment—are not isolated failures. They are manifestations of systemic dysfunction across governance, finance, and operations. Yet, in the face of such adversity, the country must resist the urge to adopt reactionary solutions cloaked as reforms. The call to privatize ECG may appear pragmatic at a glance, but without addressing the deeper institutional weaknesses, such a move risks becoming a political convenience rather than a sustainable solution.

This article has shown, through data-backed analysis and comparative global insights, that performance failure in public utilities is not intrinsic to public ownership, nor is efficiency an automatic outcome of privatization. What determines success is structure, strategy, and the political will to enforce discipline and transparency. As case studies from Brazil, Singapore, Morocco, and Kenya have shown, utilities can achieve operational excellence through hybrid models that blend strategic state oversight with performance-driven private participation. These models prioritize results, not ideology, and place the public interest at the center of utility reform.

The proposed four-tiered restructuring model for ECG offers a realistic and context-appropriate blueprint. It separates oversight from operations, stabilizes forex exposure, incentivizes private sector efficiency through regional franchises, and embeds transparency through digital audit infrastructure. When aligned with broader value chain reforms, such as renegotiating power purchase agreements, depoliticizing tariff-setting, and enhancing regulatory independence, this model can redefine energy governance in Ghana. Equally important is the need for leadership that does not shy away from difficult decisions. Reforming ECG and the wider energy sector will require confronting entrenched interests, enforcing contracts, demanding performance from appointees, and investing in long-term capacity building. But it is these very actions that will lay the foundation for energy reliability, investor confidence, and national sovereignty.

As Ghana pursues its ambitions to become a regional hub for industrialisation, digital transformation, and green growth, a reliable and financially stable electricity sector will be the cornerstone of that future. The power sector cannot continue to be a fiscal drain, a political pawn, or an afterthought. It must become a driver of inclusive development and economic resilience. To the policymakers, regulators, energy experts, and citizens of Ghana, the time to act is now. The era of window dressing and cyclical crisis management must end. It is time to fix power, not shift blame. Ghana deserves a 21st-century energy utility—efficient, accountable, sovereign, and designed for the future. Reform is no longer optional. It is a national imperative.

*******

Dr David King Boison, a maritime and port expert, AI Consultant and Senior Fellow CIMAG. He can be contacted via email at kingdavboison@gmail.com

Cynthia Morkoah Agyemang (Mrs) is a Banking Professional & Applied Mathematics Researcher. She can be contacted via email at mornantyberry@gmail.com

Iddrisu Awudu is a Professor of Management: Supply Chain and Logistics. He can be contacted via email at Iddrisuawudukasoa@gmail.com

Latest Stories

-

Kristi Noem’s bag with $3,000 stolen from DC restaurant

24 minutes -

‘You’re crippling the mining sector’ – Minority criticises government over new policies

36 minutes -

Harvard University sues Trump administration to stop funding freeze

1 hour -

KNUST Homestay Experience fosters joy and cultural exchange for international students

3 hours -

KCCR study raises alarm on antimicrobial resistance in Kumasi

3 hours -

Families cap Easter festivities at Luv FM Family Party in the Park

3 hours -

Nacee, Empress Gifty, Tagoe Sisters, others light up Grand Arena at MTN Stands in Worship 2025

3 hours -

Adabraka wins 10th Sheikh Sharubutu Ramadan Cup

4 hours -

Burnley promoted back to Premier League with win over Sheffield United

4 hours -

Why treason may not be an offence in Ghana

4 hours -

Leeds United promoted back to Premier League

4 hours -

CAF holds draw for African Schools Football Championship 2025

4 hours -

Binduri MP condemns violent attacks after killing of woman, 4 children

4 hours -

St. Patrick’s Hospital receives GH₵100,000 worth of anti-malaria drugs from Bliss GVS Pharma

4 hours -

Full text: Lands Minister updates on gov’t sustained fight against illegal mining

6 hours