On the first day of trading after the extended post-Ramadan break, Indonesia's IDX stock exchange was forced to close five minutes after it opened today (April 8), falling by 9.2 percent in response to deep concerns over US tariffs and deeper structural issues including a falling rupiah, erratic presidential policies, budgetary overspending, rising state-owned enterprise debt and the growing presence of the military in government.

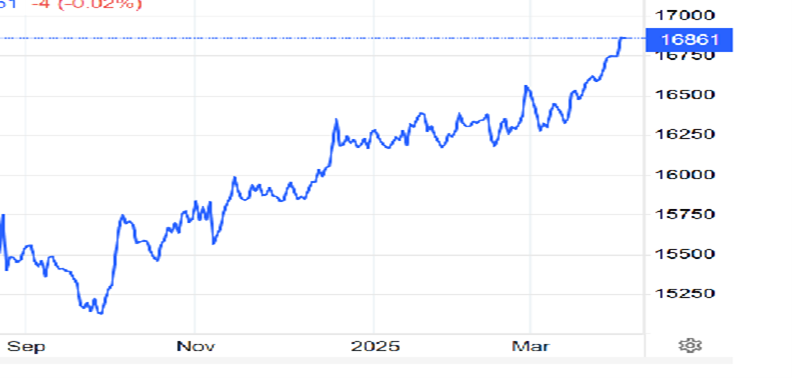

The Jakarta Stock Exchange (IDX) reopened after 30 minutes, recouping some of its losses but closing down by 546 points, or 8.5 percent, at 3 pm, to 6008.5. But the prognosis is for continuing market upheaval after having fallen by 22 percent, from a high of 7905 last September 19. The rupiah has fallen by more than 10 percent from its September 24 high of 15,130 to hit Rp17,261 to the dollar, requiring Bank Indonesia on April 7 to intervene to stabilize the currency’s value amid disruptions in global financial markets.

The US tariff hikes on April 2 and China’s retaliatory tariffs on April 4 have triggered capital outflows and weakened the currency of emerging markets, not just Indonesia’s, but Jakarta was already in the midst of a tailspin when the tariffs were announced.

US President Donald Trump imposed a 32 percent tariff on Indonesian exports to the US, expected to go into effect on April 9, due to a trade surplus in Indonesia’s favor of US$17.9 billion, on US$28.1 billion in joint trade, primarily in footwear, clothing, machinery, and electrical equipment. The palace in Jakarta said it wouldn’t retaliate, announcing it would instead pursue negotiations with the US Trade Representative and other agencies. Coordinating Minister for Economic Affairs Airlangga Hartarto said the decision to not retaliate was made with a view to protecting long-term bilateral trade relationships.

"The approach was taken to safeguard the investment climate and maintain national economic stability," Airlangga said in a written statement on April 6. He added that President Prabowo Subianto had instructed the government to issue an official response to Washington DC, and prepare a trade delegation for further talks.

The United States ranks as Indonesia's second-largest trading partner after China, with 11.2 percent of exports by value going to the US. Indonesian imports from the United States were US$11.34 billion, although that figure doesn’t represent intangibles the US records on its services account including non-merchandise revenues of Google, Microsoft, Apple, Meta, and lesser players, not to mention royalties generated by the likes of McDonald’s, Coca-Cola and other globalized US brands.

It’s uncertain what action Indonesia could take in the face of uncertainty over the Trump-caused upheaval of the global trading regime. Governments all over the planet face plummeting markets in the midst of the chaos, scores of them rushing delegations to Washington to plead for relief.

Indonesian rupiah to US dollar

“The tariffs can trigger a recession for the Indonesian economy in the fourth quarter of 2025," Bhima Yudhistira, Executive Director at the Center of Economic and Law Studies, told local media on April 3. The economy had been projected to grow by around 5 percent this year, but given growing uncertainty, it’s unsure whether that target is attainable. Hendra Sinadia, Executive Director of the Indonesia Mining Association, told reporters on April 6 that demand for Indonesian natural resources is expected to decline if the global industrial sector contracts as a result of the US tariffs.

But Jakarta has problems of its own making, many of them generated by Prabowo. The benchmark IDX Composite Index plummeted so sharply on March 18 that officials also halted trading for 30 minutes, the market’s worst performance since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic.

A combination of domestic issues has eroded investor confidence including a series of government policies implemented without adequate risk mitigation. Analysts are urging the government to take immediate recovery measures to prevent a deeper collapse. The state budget deficit as of February reached Rp31.2 trillion, with debt interest repayments totaling Rp79.3 trillion in the first two months. The rising debt burden could hinder productive government spending, preventing the economy from receiving optimal stimulus.

Since taking office last October 1, Prabowo has launched a universal school lunch program whose costs are projected to reach Rp420 trillion (US$25.90 billion), more than 10 percent of the entire US$226 billion equivalent fiscal budget by the end of the year. He is also backing a massive US$60 billion seawall to protect Jakarta from sinking, and has continued downstreaming of resource-based industries and other programs. Former President Joko Widodo’s stalled Kalimantan government capital, Nusantara, remains an expensive project and its completion feels increasingly uncertain.

Estimates from 2023 suggest that Indonesia's six biggest construction SOEs collectively faced debt of over Rp1,000 trillion (US$62.8 billion), an average of US$11.3 billion per company, which is likely to severely limit their ability to invest in new projects and technology. The debt is largely driven by Jokowi’s use of SOE borrowing to fund numerous expensive infrastructure projects, including Nusantara, during his decade in office.

Prabowo has raised other concerns, however, including, as Asia Sentinel reported on February 28, the steady blurring of the lines between an elected civilian government and the military, the TNI (Tentera Nasional Indonesia). In March, Indonesia's parliament passed revisions to the country's military law, allocating more civilian posts for active military officers as students and activists protested against the legislation, saying it could take the country back to the draconian 'New Order' era of former strongman President Suharto, when military officers dominated civilian affairs. Prabowo, a Special Forces commander under Suharto, is steadily expanding the armed forces’ role in what were considered civilian areas, including his flagship free meals program.

Here comes Danantara

Then there is Daya Anagata Nusantara Investment Management Agency, or Danantara, the new sovereign investment fund launched by Prabowo with a mission to put the economy into hyper drive. It is initially designed to oversee a fund of approximately US$20 billion, a figure expected to rise to US$900 billion, with plans to invest in more than 20 strategic projects including nickel downstreaming, artificial intelligence and renewable energy. Modeled after Singapore's Temasek, Danantara has been given control of the assets of all SOEs and it has raised concerns about potential political interference and governance issues, given its close ties to Prabowo and other vested interests.

“I think the problem is that Prabowo's government is rife with conflicts of interest,” said a western businessman. “Danantara's CEO Rosan Roeslani is concurrently Minister of Investment, a clear conflict of interest. He is a one-time crony of the Bakrie family. The COO is the nephew of Luhut Binsar Pandjaitan, the powerful coordinating minister for Maritime Affairs and Investment under Jokowi and currently chairman of the National Economic Council. The feeling is that this is more like Malaysia’s corrupt 1MDB than a proper fund with transparent governance.”

The real sector is also under significant pressure, as evidenced by widespread layoffs and an increase in non-performing loans (NPLs), which rose to 2.17 percent in January 2025 from 1.9 percent in 2024. This indicates weakening consumer purchasing power and rising banking risks. Meanwhile, the continued depreciation of the rupiah has added pressure on companies with US dollar-denominated debt exposure.

From this vantage point, it appears the Trump tariffs may ultimately be too much for Jakarta to bear.

It's all fun and games when it comes to the born-moron Donald Trump and his completely dumbass tariffs. In both economic theory and policy terms, the effects have proven near fatal, especially for the small, emerging economies and those in ASEAN that have built their economies on mountains of sand; i.e. structural and institutional contradictions that are deeply embedded in their political governance, societies and of course their export-dependent economies. Now of course every country would be sitting down and wondering what will -- not might -- come after the diot Trump's "90-day pause" on applying his tariffs (pity China, eh?). For one thing, there's will be new mutations in the new international division of labor that has been through various iterations and revisions since, in this century so far, the 9/11 criis, the 2008 crisis, the 2018 crisis, the Covid crisis and the Trumpite-inspired crisis. And it is a crisis. It'll speak much, I would think, about the nature of each country's capitalism as well as its capitalist development based on whatever growth it can eke out from the Trumpite Tariffs carcass that's still in formation.

For me, it'll be interesting to watch Prabowo's Daya Anagata Nusantara Investment Management Agency, or Danantara, and how it'll work, how he manages it, what internal contradictions it produces and the struggle for state power between the various invested classes. I get the uneasy feeling it could turn out to be something like Malaysia's totally disastrous 1MDB fiasco. Too many crooks stirring the pot.