Depending on which metrics you look at, there is an argument that China is on track to fulfil its ambition to eclipse the US and become a world leader in artificial intelligence by 2030.

Research shows that not only was the Asian superpower the biggest producer of AI talent globally in 2023, it also dominates AI patents, accounting for 61 per cent of global patent origins in 2022.

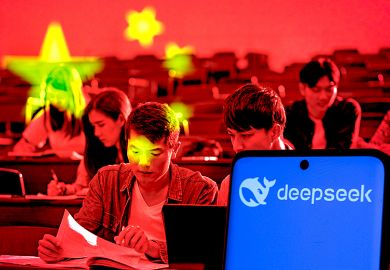

The buzz around China’s AI capabilities has grown louder this year, with the release of AI chatbot DeepSeek – a model developed in China by homegrown talent that appears to rival the performance of ChatGPT for a significantly lower cost.

In other areas, however, China lags behind the US, including in high-impact research and the number of notable AI models it produces. According to researchers at Stanford University, in 2023, 61 of these models were produced by US-based institutions and 21 by those from the European Union. In comparison, China produced 15.

A key differentiator between China and the US is their attitudes towards the role academia plays in driving technological advances. The question is whether China’s heavier reliance on universities will give it the edge it needs to catch up with and surpass its American rival – or whether its top-down tendencies will always leave it playing catch-up.

China’s AI ambitions as we know them today date back to 2017, when the state outlined its plan to position the technology as the main driving force of industrial transformation. The landmark document, released by China’s state council, explicitly called for the creation of “mass AI innovation bases” that link universities and enterprise.

However, around the world, AI research is largely taking place in private companies, rather than academia. As authors of the 2024 AI Index Report wrote, “escalation in training expenses has effectively excluded universities, traditionally centers of AI research, from developing their own leading-edge foundation models”.

Despite this, China has pushed to develop a holistic ecosystem, explicitly recognising the vital role academia plays in achieving the country’s ambitious national goals. While the state has specifically backed leading technology companies, including Alibaba, Baidu and Tencent, as AI “national champions”, the expectation is that this group will work in tandem with universities.

“In the West, we tend to see companies essentially as a vehicle for shareholders and management to make money,” said Rogier Creemers, a lecturer in modern Chinese studies at Leiden University. “In China, let’s just say that there’s a slightly different political attitude to that. It’s all perfectly fine for you to make a bit of money running a company, but you’re also a Chinese company, and that means that you are expected to support the government in the realisation of its development goals.”

As shown by the treatment of technology giants in the late 2010s, when they were hit with heavy regulation and antitrust cases, the threat of crackdowns is never far away in China. And this is a powerful incentive to comply, Creemers argues. “If the government asks you…to help ensure that the university ecosystem remains healthy, you better do that,” he said.

The sticks are also reinforced with carrots: “In the West, we by and large think the market will solve problems: companies need to pay for the skill sets that they need and then the market will provide those skill sets,” said Creemers. “In China, there’s much more of an effort to make things easy for companies.”

The education ministry has the final say on what programmes are offered at public universities, and officials focus on ensuring an adequate talent pipeline into the workforces of industries it sees as critical to the country’s future. And for Chinese universities, that has translated into “massive investment” by the state in their AI programmes, said Ruibin Bai, professor and head of the Artificial Intelligence and Optimisation Research Group at the University of Nottingham Ningbo China.

“In the past few years, nearly all universities in China have experienced heavy investment in AI. As a result, you see a dramatic expansion in the staff recruitment,” he said. This is particularly true of public universities, but independent ones like Nottingham Ningbo have also benefited from government grants, he said.

In recent months, leading Chinese universities have announced plans to further expand undergraduate enrolment in key areas, including courses related to AI. China’s top university, Tsinghua, also plans to open a new college that focuses on “the deep integration of academia and industry in AI”.

The challenge for teaching is to keep up with the fast pace of development happening in the private sector – to which end the Chinese government has encouraged better integration between universities and industry. “While traditional curricula often lag behind cutting-edge developments…leading Chinese universities are shortening this gap through joint labs with companies,” said Marina Zhang, an associate professor at the Australia-China Relations Institute of the University of Technology Sydney (UTS).

For Bai, it’s a case of striking the right balance. “It’s impossible to teach all the latest technologies,” he said. “You want to lay a good foundation but also get [students] exposed to the latest [technologies].”

Another key challenge for China is retaining talent. The US remained the top destination for top-tier AI talent to work in 2023, according to MacroPolo, a thinktank within the US Paulson Institute. However, it also found that China produces the most AI talent, and an increasing proportion of it is staying and working locally.

This is likely to be due to both push and pull factors. The growth of China’s reputation as a research powerhouse coincided with Donald Trump’s China Initiative, launched during his first presidential term in 2018, to root out suspected Chinese spies in American research and industry. And Trump’s return to the White House has already seen some influential researchers flee the US – decisions that are often highly publicised in Chinese state media.

“You could argue that Trump, in a way, is a godsend for the Chinese ecosystem by making the United States a vastly less attractive place for Chinese scholars and engineers and experts to go,” said Creemers.

Even when researchers return to China, however, academia may not be their destination. As is the case across the world, Chinese universities have historically found it “very difficult to compete with industry to hire top talent”, said Bai. Private companies “outpay universities, provide better career paths, and are doing projects that could sound more cutting edge and at a much larger scale”.

Yet recent rounds of redundancies in the private sector mean that industry jobs are looking less appealing than they once did, Bai added. “There are [now] people who are coming to academia from industry,” he said. “I think there’s a good balance now compared to before.”

Meanwhile, in the research space, while private companies are often focused on getting new AI models out as soon as possible, universities are also supporting the long-term development that will be crucial to China’s enduring success.

“Chinese universities account for a majority of government-funded basic research projects, exploring emerging frontiers [such as quantum machine learning] with a 10- to 15-year horizon,” said the UTS’ Zhang.

“This fundamental work underpins industry breakthroughs. Historically, many transformative AI ideas...emerged from academic labs. Hence, robust university research is…essential for sustaining China’s competitiveness amid global technology competition.”

– Helen Packer

The chips are up, but challenges remain

Even before Donald Trump returned to the White House in January, the US-China war over AI had disrupted long-standing academic and research collaborations, particularly in semiconductor and machine learning research.

Many of China’s elite universities previously relied on partnerships with top American institutions to access state-of-the-art AI technologies, faculty exchanges and joint research grants. However, the Biden administration’s introduction of the CHIPS and Science Act in 2022, and subsequent restrictions on Chinese access to advanced computing technologies, have forced China’s elite universities to seek alternative pathways in pursuit of the country’s ambition to become a superpower in AI and emerging technologies by 2030.

The question is whether this will be enough to compensate for the loss of Western ties and technologies. And that is a particularly vital issue in the context of this year’s renewal of China’s university excellence initiative, known as the Double First-Class project, which supports nearly 150 elite universities to conduct world-leading research.

The level of endeavour is certainly impressive. Since 2023, Chinese universities have accelerated domestic AI talent cultivation, interdisciplinary research and technological development. Many AI-related undergraduate and graduate programmes have been introduced. Specialised research centres have been established. And partnerships with domestic tech giants have been expanded.

For instance, Tsinghua University has introduced 38 AI-related electives and invested in AI-powered research platforms to drive innovations in machine learning and computational sciences. It will soon launch an interdisciplinary AI Academy that integrates AI with mathematics, physics and engineering.

Similarly, Shanghai Jiao Tong University has increased its undergraduate intake in AI and integrated circuits, while establishing an AI research institute dedicated to fundamental breakthroughs in deep learning algorithms and computing architectures.

Meanwhile, Xi’an Jiaotong University has expanded its “AI+X” professional framework, integrating AI with biomedicine, information technology and new energy storage systems. This approach reflects a broader national trend: rather than treating AI as an isolated discipline, universities are embedding it across diverse academic fields to foster cross-sector innovation.

Deeper alliances have also been formed with domestic technology firms, AI startups and semiconductor manufacturers. For example, Huawei has partnered with several Double First-Class universities to develop AI chip research initiatives, helping to overcome China’s dependency on foreign semiconductor technology.

Additionally, Alibaba’s DAMO Academy and Tencent’s AI Lab have increased funding for university-led AI projects, emphasising natural language processing, computer vision and cloud computing applications. These companies have also co-developed AI-focused curricula, internship programmes and talent pipelines, ensuring that graduates are equipped with the technical expertise needed to drive China’s AI ambitions.

One of the most notable recent developments is the emergence of DeepSeek, a cutting-edge AI model that is seen as a serious rival to ChatGPT and other US technologies. While primarily developed by industry leaders, DeepSeek has also benefited from academic contributions, with researchers from Tsinghua, Peking and Zhejiang universities involved in refining its language models and training datasets. These universities have provided computational expertise and theoretical insights, deepening the collaboration between academia and industry in China’s AI ecosystem.

As academic exchanges with the US have diminished, Chinese universities have redirected their international collaborations toward ASEAN and BRICS nations. One notable example is the NexT Research Centre, a joint initiative between Tsinghua University and the National University of Singapore (NUS) – which now also includes the University of Southampton – to advance AI-driven applications in healthcare, finance and smart cities.

Meanwhile, Peking has been actively engaging in AI ethics and governance through various initiatives, including collaborations with European institutions. These efforts highlight China’s increasing involvement in global discussions on AI governance, particularly in areas that are less affected by US sanctions.

Yet several challenges persist. One is ensuring the quality of AI education amid rapid expansion. Many top universities have significantly increased undergraduate and graduate enrolment in AI-related disciplines, but without a proportional increase in faculty recruitment, research funding or laboratory infrastructure.

Relatedly, China’s AI research output, while growing in volume, still struggles to achieve global impact in terms of citations and patents. And while Chinese universities have produced some of the world’s most-cited AI research papers, their ability to translate academic research into globally competitive products remains an area for further development.

In addition, China continues to face a talent retention challenge. Although visa restrictions have reduced outbound mobility to the US, many highly skilled Chinese AI researchers are relocating to European and Singaporean institutions, where research environments are perceived to be more open and better funded.

Hence, sustaining the Double First-Class universities’ momentum in the AI race requires sustained investment in faculty, research and policy, balancing expansion with academic quality. Even then, it remains an open question whether technological bottlenecks and talent mobility challenges can be entirely overcome.

The answer will shape not only China’s higher education landscape but also the global AI ecosystem in the years to come.

Futao Huang is a professor in the Research Institute for Higher Education at Hiroshima University, Japan.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login